|

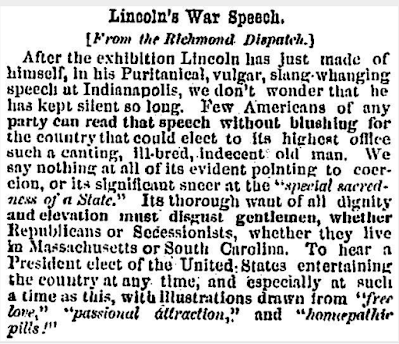

| Charleston Mercury, February 16, 1861. Mr. Bret Stephens was not available to complain about how unkind and divisive Lincoln had been, so they had to do it themselves. Reminds me of Biden how they complain that Lincoln doesn't feed the press often enough and that he's an 'indecent old man". |

The other day, I was comparing Biden's September 1 speech to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union, and the Four Freedoms peroration. Today, Mr. Bret Stephens, stealing a David Brooks lede ("With Malice Toward Quite a Few"), decides to up the ante:

Abraham Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address was a 3,600-word olive branch to a South on the eve of the Civil War. His second promised malice toward none after the war left 620,000 dead. Americans have long revered both speeches because they offered a measure of redemption, and a means of reconciliation, to those who deserved it least.

Joe Biden’s speech in Philadelphia last week bears no resemblance to either address, except that, in his own inaugural, he staked his presidency on ending “this uncivil war that pits red against blue.” So much for that. Like the predecessor he denounces, Biden has decided the best way to seek partisan advantage is to treat tens of millions of Americans as the enemy within.

(First sentence in the second paragraph is screaming for an editor: an expression in Biden's inaugural address is not a feature of last week's speech—at some point in composing the sentence he decided it was about all of Biden's speeches, but was too lazy to reread the first seven words.)

Noteworthy, as Erik Loomis says, that Stephens is now agreeing that the Republican Party is the Confederacy. I mean, why else would he be urging Biden to treat the former the way Lincoln treated the latter?

When you think about it, it's worth looking at the analogy in some detail, and also looking at the Lincoln speeches, another thing Mr. Bret is too lazy to do, especially the First Inaugural, which none of us have read as much as we probably should.

This was March 4, 1861, four months after the election. Seven mostly deep-South cotton states had announced their secession from the Union, unconvinced by Lincoln's assurances throughout the campaign and afterwards that the new Republican government had no designs on slavery, and spends most of the speech repeating those, I guess in the hope of reaching the slave states still on the fence, Virginia and North Carolina, Arkansas and Tennessee:

Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that—I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so....

He accepts the right of each state to decide whether it permits slavery within its borders or not; will not interfere with the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act (though not the capture and enslavement of free Blacks); and promises not to challenge the traditional compromises allowing slavery in Oklahoma and the Mexican conquests from New Mexico to Utah and forbidding it from Nebraska to the Dakotas.

What he can't accept, however, is the idea of secession from the Union, which he defends with a weird kind of version of St. Anselm's ontological argument for the existence of God (a "being than which no greater can be conceived" must exist, because if it didn't exist, it wouldn't be that great):

the proposition that in legal contemplation the Union is perpetual [is] confirmed by the history of the Union itself. The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774. It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured, and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was "to form a more perfect Union."

But if destruction of the Union by one or by a part only of the States be lawfully possible, the Union is less perfect than before the Constitution, having lost the vital element of perpetuity.

And therefore he must and will continue to be the president of the United States for the next four years, taking care that the laws be faithfully executed in all of them:

I trust this will not be regarded as a menace, but only as the declared purpose of the Union that it will constitutionally defend and maintain itself.

In doing this there needs to be no bloodshed or violence, and there shall be none unless it be forced upon the national authority. The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere.

That is some kind of a menace, though. Not exactly addressed to the actual secessionists, since Lincoln makes a rather Bidenesque show of not having anything to say to them at all:

>That there are persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union at all events and are glad of any pretext to do it I will neither affirm nor deny; but if there be such, I need address no word to them. To those, however, who really love the Union may I not speak?

But a vague warning to the people in general, of anarchy, which to Lincoln means the end of democracy in the seceding states:

Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible. The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism in some form is all that is left.

This is a loopy text, in more ways than one. The analytic commentary on it is weak, I think, unable to deal with how strange it is, acting as if it's just a list of policy points like a Bill Clinton speech, but it really isn't.

It literally loops, in fact, around a set of themes that aren't quite related to each other—his promises not to disturb the South if permitted to exercise his authority (he'll let them name their own federal civil servants) and in particular not to disturb the slave economy; his invocations of the guidance of the Constitution, which sometimes lead him into gnarly territory (a mild challenge to the concept of judicial review, which must be aimed at Chief Justice Taney: "I do not forget the position assumed by some that constitutional questions are to be decided by the Supreme Court", and a speculation on the possibility of calling for a constitutional convention); appeals for calm in the face of what clearly is a very serious crisis; and a defense of democracy as the inevitable cure:

Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world? In our present differences, is either party without faith of being in the right? If the Almighty Ruler of Nations, with His eternal truth and justice, be on your side of the North, or on yours of the South, that truth and that justice will surely prevail by the judgment of this great tribunal of the American people.

The thing it's really about, it seems to me, is the prospect of war; a word he only uses twice in the whole thing, once in a list of ways in which life will be odd in a disunited nation, and how futile a war would be—

A husband and wife may be divorced and go out of the presence and beyond the reach of each other, but the different parts of our country can not do this. They can not but remain face to face, and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them. Is it possible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory after separation than >before? Can aliens make treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more faithfully enforced between aliens than laws can among friends? Suppose you go to war, you can not fight always; and when, after much loss on both sides and no gain on either, you cease fighting, the identical old questions, as to terms of intercourse, are again upon you.

—and once at the almost very end, where he does address the secessionists in spite of his claim that he has nothing to say to them, and loops back to the theme of how if there's violence it will be their fault, not his:

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. ">You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend it."

After which comes the only bit of the speech that David Brooks or Bret Stephens has actually read, the stuff with the "mystic chords" and the "better angels". Turns out this wasn't even Lincoln's idea, but that of secretary of state William Seward, who felt the speech needed to end on a note of hope. Seward drafted a paragraph

I close. We are not, we must not be, aliens or enemies, but fellow-countrymen and brethren. Although passion has strained our bonds of affection too hardly, they must not, I am sure they will not, be broken. The mystic chords which, proceeding from so many battlefields and so many patriot graves, pass through all the hearts and all hearths in this broad continent of ours, will yet again harmonize in their ancient music when breathed upon by the guardian angel of the nation.

and Lincoln, apparently a genius editor (who knew?), tweaked it as hard as he could tweak, creating the immortal soundbite:

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

But that's not an "olive branch", whatever Seward may have meant. Transfigured by Lincoln, it's a prophecy that the Union will win, and once you get this, the whole speech begins to look like a challenge, as much as '"Come at me, bro!" He's ordering the enemy to calm down, he's not offering anything to the disgruntled South that he hasn't been offering since 1856, he's explaining that he's in the right legally and morally, and he's telling them war won't accomplish anything and the Union will triumph in the end.

The Republican New York Times understood it pretty well:

But still we would say to our people, for the present, keep cool, and bide your time. The honor of this State is no further involved in this matter. It has been transferred to the shoulders of the Government of the Confederate States of America. Whether wisely or not, it is now too late to discuss. Our course now is one entirely of policy and war strategy. We do not profess to be accurately cognizant of the plans of President DAVIS. If there is to be war, there must be a plan and a policy for the campaign. These must originate from the heads of the Government. We have now nothing to lose by time -- everything to gain.

So did the Southern papers:

Newspapers reacted to Lincoln’s inaugural address the next day, and the reactions varied based on political and geographical affiliation. Most Confederate newspapers asserted that Lincoln had revealed his true intention to force them back into the Union. The Montgomery (Alabama) Weekly Advertiser declared: “War, and nothing less than war, will satisfy the Abolition chief.” Fire-eater Robert Rhett, editor of the Charleston Mercury, wrote: “It is our wisest policy to accept the Inaugural as a declaration of war.” Another Mercury editorial opined: “A more lamentable display of feeble inability to grasp the circumstances of this momentous emergency, could scarcely have been exhibited.” A correspondent considered the address from “the Ourang-Outang at the White House” to be “the tocsin of battle” and “the signal of our freedom.”

Tone sound familiar, at all? I don't get the impression that any nonpartisan

papers came out to lament how Lincoln's elitist contempt for the simple-minded

slavers left them no choice, either. The situation was just as The Times

had put it, waiting for the insurgency to make its move or stand down. On

April 12, the Confederacy in South Carolina decided to defy Lincoln's warnings

and attack the Union installation at Fort Sumter, and shortly afterwards,

Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee joined the rebellion.

Biden's inaugural speech was nothing like this, even though it was just a

couple of weeks after our own Fort Sumter, the violent attack on the Capitol,

and less than a week before Trump's Senate trial for his role in the matter in

the second impeachment, in which a failure to convict (which the press would

call an "acquittal") was guaranteed; there were really too many other things

going on, between the pandemic and the economic crisis. It was also just a

couple of weeks after the special election in Georgia gave Democrats a kind of

control over the Senate (enough votes to elect a majority leader or pass a

budget reconciliation bill, anyway, or theoretically end the filibuster),

opening up a truly thrilling prospect that rebuilding after the

catastrophes of 2020 could really be "building back better". And the COVID

vaccine was finally starting to get distributed (January 22 was the day the

number of Americans with a first shot reached a million).

So if there was ever a time for a speech "looking forward" rather than backward, this was it. The idea that January 6 might have been the beginning of something rather than the last gasp of Trumpery hadn't started to sink in.

Now it really has sunk in for many of us, thanks very much to the work of the House select committee on January 6, and now was the time for Biden to deliver a speech like Lincoln's First Inaugural, which is what he did in Philadelphia. It's even loopy in a way like the Lincoln speech—ill-shaped, I thought when I was watching it, but now I think multifocal, moving around a few main themes in an unconventional way—the danger of the "MAGA Republicans"; the extension of welcome to those remaining Republicans who respect the Constitution, the rule of law, and the "will of the people"; and his own constitutional responsibilities as president.

He also took a moment to draw his own political red line, like Lincoln making it clear that there was not going to be any further slavery to the north and west, on the compromises he's not prepared to make with Republicans in general:

MAGA forces are determined to take this country backwards — backwards to an America where there is no right to choose, no right to privacy, no right to contraception, no right to marry who you love.This short paragraph is the bit that puts Stephens in such a rage:

As categories go, this one [of MAGA Republicans] is capacious.

It includes violent Oath Keepers and Proud Boys — as well as every faithful Catholic or evangelical Christian whose deeply held moral convictions bring them to oppose legalized abortion.

It takes in the antisemites who marched at Charlottesville — as well as socially conservative Americans with traditional beliefs about marriage, which would have included Barack Obama during his 2008 run for president.

It encompasses undoubted election deniers like lawyers Sidney Powell and John Eastman — along with ordinary Americans who have been bamboozled into harboring misguided but sincere doubts about the integrity of the last election.

But that just seems like a completely dishonest and wrong reading to me (not least in the backhanded reference to Obama, whose support of same-sex marriage goes back to 1996, though he clearly felt it should be off the table in 2008 beacause the country wasn't ready for it), much as if you were to accuse Lincoln of declaring war against the people of Maryland, as well as Virginia and North Carolina and the other hesitant states, when he insists he won't allow the extension of slavery into the territories where it is illegal. Biden is very clear and emphatic in defining the MAGA Republicans

And here, in my view, is what is true: MAGA Republicans do not respect the Constitution. They do not believe in the rule of law. They do not recognize the will of the people.

They refuse to accept the results of a free election. And they’re working right now, as I speak, in state after state to give power to decide elections in America to partisans and cronies, empowering election deniers to undermine democracy itself.

and then loops into offering illustrations (for Democrats) of why the majority of Americans should feel especially threatened by these extralegal plots, not just because they're extralegal but because they threaten our majority will.

If you wanted to vote in 1861 to retain slavery in Maryland, you were entitled to do so, as far as Lincoln was concerned, and so he repeatedly said; it was only if you entered into rebellion against the United States that you had to be stopped. If you want to vote to ban abortion in Kansas, Biden understands, that is your right—but if your side loses you have to accept that it's over, you can't move to getting your way by instituting minority rule. It's important!

Those who would interfere with the peaceful transition of power have put themselves beyond politics, on a war footing. This is not your fun little game you guys thought you were signing up to write about. It's a serious threat to our country, and I'm glad she mentioned it.

— Three Blog Night (@Yastreblyansky) September 8, 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment