|

| Frontispiece from Matthew Hopkins' The Discovery of Witches (1647), showing witches identifying their familiar spirits for the Witch Finder. Via Wikipedia. |

Hi, it's Stupid to criticize Justice Alito for citing a 17th-century jurist just because the jurist, Lord Edward Coke, happened to be an advocate of marital rape and had ordered women to be executed for witchcraft. After all, marital rape and the execution of witches are deeply rooted in our nation's history and traditions too! Besides, why should we suppose his views on these matters are even relevant in any way to his views on abortion?

Alito notes that

The “eminent common-law authorities (Blackstone, Coke, Hale, and the like),” Kahler v. Kansas, 589 U.S. __, —_ (2020) (slip op., at 7), all describe abortion after quickening as criminal. Henry de Bracton's 13th-century treatise explained that if a person has “struck a pregnant woman, or has given her poison, whereby he has caused an abortion, if the foetus be already formed and animated, and particularly if it be animated, he commits homicide.” H. Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae...

Although what Coke says, in fact, contra Bracton, is that it is not homicide, unless the child dies after being born, because while within the womb the fetus isn't really a person, a "reasonable creature", a thing in rerum natura, in the world of natural beings, and under the King's peace, that is a member of society:

If a woman be quick with childe, and by a potion or otherwise killeth it in her wombe, or if a man beat her, whereby the child dyeth in her body, and she is delivered of a dead childe, this is great misprision, and no murder; but if he childe be born alive and dyeth of the potion, battery, or other cause, this is murder; for in law it is accounted a reasonable creature, in rerum natura, when it is born alive.

I went into this membership in society question in more philosophical than jurisprudential detail in a quarrel with Ross Douthat in December:

All the exceptions to the rule of homicide are about membership: the hangman can kill the prisoner because the prisoner is an outlaw, the soldier can kill the enemy because the enemy is one of them and not one of us. It's not nice, and it's better to be a liberal and against killing anybody, because we're all of the human "race", but that's the same principle. The rules for unplugging the brain-dead and the vegetative are on the same basis—will we ever be able to interact with them again?—and a social interaction in their own right, as we consider the wishes they expressed in a living will.

The fetus is really not a person, in this view, and I'm pleased to be able to note that all the lions of English common law agree with me, even the witch burners:

The proposition that abortion cannot be homicide is reiterated by practically every major writer on English criminal law, from William Staunford and William Lambard in the sixteenth century, through Edward Coke and Matthew Hale in the seventeenth century, to William Hawkins and William Blackstone in the eighteenth century. Homicide was agreed to require the prior birth of the victim. Murder might be charged, according to Hale, if the woman on whom an abortion was performed died as a result. Murder also might be charged, according to Coke, if a botched abortion injured a fetus that afterwards was born alive and then died from its prenatal injuries. But where a fetus, even a quickened fetus, was killed in the womb, resulting in stillbirth, whatever the crime, it would not be homicide at common law.

And then before Bracton, in the Leges Henrici Primi of ca. 1115, abortion wasn't a crime at all, though it was regarded as a sin, dealt with by ecclesiastical courts, with a sentence of three years' penance before quickening, and ten years after.

One thing that really stands out for me in the little fragments of ancient case law out of which abortion jurisprudence is built is how little it has to do with the kind of abortion we are mainly concerned with, where a woman makes her own decision that she doesn't want to have this baby and seeks help with ending the pregnancy. My dudes at JRank suggests that this must be because it was so hard to score a conviction

Without reliable tests for pregnancy, testimony about fetal movement might be required to prove that a woman really had been pregnant, or that the abortion had killed a live fetus. Proof of quickening became, then, a practical if not a legal prerequisite; and the need for such proof would make it hard to prosecute a woman who had procured her own abortion. This, in fact, was seldom done.

but that seems to me to be putting it upside down. The cases we do see generally involve some violence done against the woman, as in Alito's quote from Bracton at top. where she has lost the baby because of somebody beating or poisoning her. The same goes for the most famous biblical rule, from Exodus 21:

22 “If people are fighting and hit a pregnant woman and she gives birth prematurely[a] but there is no serious injury, the offender must be fined whatever the woman’s husband demands and the court allows. 23 But if there is serious injury, you are to take life for life, 24 eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 25 burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise.

There, losing the baby isn't a "serious injury" to the woman but a tort done to the husband, who loses an heir.

Then there's the 18th-century case Alito himself cites:

In 1732, for example, Eleanor Beare was convicted of “destroying the Foetus in the Womb” of another woman and “thereby causing her to miscarry." For that crime and another “misdemeanor,” Beare was sentenced to two days in the pillory and three years’ imprisonment.

Another case is hidden in a mystifyingly wrong reading by Alito:

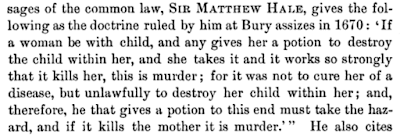

That the common law did not condone even pre-quickening abortions is confirmed by what one might call a proto-felony-murder rule. Hale and Blackstone explained a way in which a pre-quickening abortion could rise to the level of a homicide. Hale wrote that if a physician gave a woman “with child”a “potion” to cause an abortion, and the woman died, it was “murder” because the potion was given “unlawfully to destroy her child within her.” 1 Hale 129-130 (emphasis added). As Blackstone explained, to be “murder” a killing had to be done with “malice aforethought, either express or implied.”

But it's not a case of when an abortion is murder, it's a case of when botching an abortion is murder; it's the woman's death that is at issue, not that of the fetus. If the abortion is successful, there's nothing to prosecute, even though Hale thinks it's "unlawful" and Blackstone calls it "malicious". If you kill somebody when giving them an abortion, Hale says, you must "take the hazard" that it will go wrong—Alito leaves that bit out, of course.

So we can at least be certain English jurists in the 17th and 18th centuries did not think of the fetus as a person—they thought of abortion as immoral, and a "misprision", but they did not think of the fetus as its victim. If it survived long enough to get born and then died, it could be a victim, and its mother could be a victim, and was in most of the prosecuted cases, but if it died in the course of the procedure, that wasn't a criminal case. Period.

Link to Part IV.

No comments:

Post a Comment