Happy International Labor Day!

Krugman sticks this thing ("Education has less to do with inequality than you think") under his "Wonking Out" rubric, which is a shame, because that means a lot of people who need to read it won't, and since it's indirectly making a point I've been making for a long time, but making it with an expertise I couldn't come close to, I wanted to highlight it.

His immediate purpose is to defend the idea of a broad-based program to cut or eliminate student debt, like the one Biden promised in the 2020 campaign and has recently returned to talking about; a widespread criticism of such a program is that it rewards people for doing something for which they have already been rewarded, with a college degree:

What I think I do know is that much of the backlash to proposals for student debt relief is based on a false premise: the belief that Americans who have gone to college are, in general, members of the economic elite.

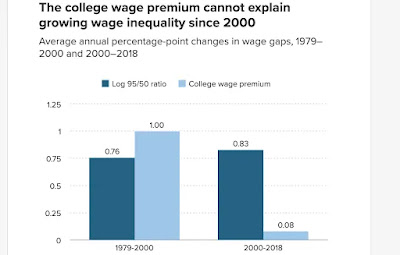

The idea being that the college loan is an investment in the future, which you make in the hope of getting richer than your neighbor who goes straight into the work force after high school. So you should be glad to pay it back. Only, as Krugman points out, that's just not true any more. One reason is the rise of ruthlessly exploitative for-profit institutions like the Corinthian Colleges, De Vry University, and the University of Phoenix with low academic standards and no follow-through. Another is the sheer difficulty of finishing if you don't borrow huge amounts and try to stay alive by washing dishes and the like as we did back in the day—40% of loan recipients never get degrees at all. But the main thing is that a college degree just isn't a ticket to prosperity any more, and hasn't been for 20 years, because college graduates' wages haven't gone up in all that time

and real wages for a majority have actually gone down.

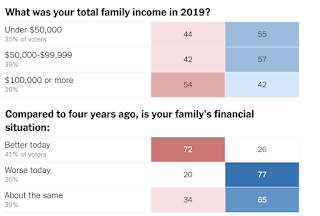

Soaring inequality has dumped the majority of college graduates into the same economic basket as their non-college coevals, which is not in and of itself a bad thing—why should managing a dentist's office be better paid than laying drywall?—but is a reason why most of them shouldn't have to pay the loans back. Because the system couldn't keep its promise, and failed them (as Millennials were telling pollsters in late 2020, the same time as they were about to come out in unexpected droves to vote for Biden). It's not their fault they have trouble paying it off.

(And by the same token, forgiveness shouldn't be applied to those for whom the system did work, not to punish them—they didn't do anything wrong—but to avoid increasing inequality.)

Anyhow, the thing I wanted to call attention to is that the same inequality phenomena are relevant to the way we do class analysis for politics: rising inequality is reconstructing a class system like that of the Gilded Age, in which educational level isn't really very significant. Most people are in the same economic boat, whether they're working with a computer or a drill bit; the most important distinction, as in the late 19th century, is in the difference between sweat income and rent income. If you're collecting rent, whether it's from a rental property, a stock portfolio, a retail or skilled labor services business, or a legal or accounting or medical practice, you are on top. If you're wholly dependent on a paycheck, you aren't. And that correlates with income far better than education does.

And age. Youth is associated with economic insecurity—which is an old American story anyway (Lincoln's idea of the normal American life-cycle in which men begin adulthood as laborers and wind up as proprietors, as in his own progress from rail-splitting to lawyering), but it's so hard to live with in the current situation in the US, where nearly a quarter of the population earns low wages (two thirds of the median, see interactive chart at top), compared with 7% in France, and you can bet a large majority of those low earners are young.

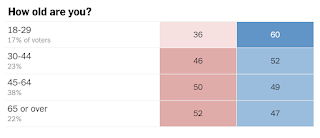

Youth is also associated with what you might call, for lack of a better term, "cultural liberalism"—comfort with diversity, interest in a wide and unpredictable variety of popular culture styles (there are plenty of white kids in suburbs and the country who listen to rap and plenty of young African Americans who are crazy about the James Bond or Star Trek franchises, what's up with that?), and relaxed attitudes about sex and drugs, and also with a weak faith in politics and government that translates into a propensity toward not voting. Do you see what I'm getting at yet? It's my usual gripe about using education (college or non-college) as a quantifiable measure of class status, which in turn is interpreted as referring to the color of your collar, and thence to the political concept of a "white working class" as the central core of the Republican party and a vague concept of "elites" and "minorities" as the constituency of Democrats. Even though we know that the main components of Republican identity are uniform whiteness, no doubt, plus higher income and higher age, while the main components of Democratic identity are ethnic diversity, lower income, and youth.

Thus in the 2020 exit polls we see non-college voters equally divided between Blue and Red

and a relatively equal division among voters over 30It's also true voters with college degrees strongly preferred Blue, as well as city dwellers and members of union households, and Evangelicals strongly preferred Red, along with rural dwellers, but we knew that already, and it's sort of baked in. Except it's further corroboration that having gone to college is not a reliable indicator of elite status. Especially since the current cohort is far more likely to have tried to get, or succeeded in getting, a college education; it's not easy to be an elite when you're in the majority.

|

| Pew, 2019. |

That's where I want to go with this: Democrats need to get past the idea that our politics is determined by a fixed set of polarizations—urban vs. rural, evangelical against other, college-educated elites and working-class stiffs—and that the only way for our party to win elections is to keep nibbling at the suburbs. There was a point in thinking that way as late as the 1990s, but things change, and that point doesn't hold any more.

Democrats must find a way of turning Millennials and Zippers into regular voters. We've tasted the results in 2018 and 2020. Does that mean a college loan forgiveness program? I don't know, though I'm pretty sure it's a good idea; it might be just as important that Joe Biden did a joint standup appearance with Trevor Noah last night. (They were both so good it hurt.) Bernie Sanders was right in principle, though his technique for achieving it turned out not to work very well: young Americans have the latent power to make a revolution against inequality, and Democrats can win by allowing and encouraging them to unlock it.

No comments:

Post a Comment