|

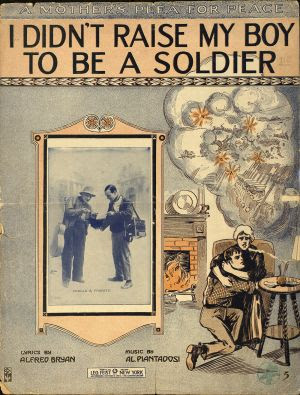

| Song sheet, 1915, via ww1online. |

It's world famous moral philosopher David F. Brooks, in his just-the-tip wokeness phase, looking for a morally more satisfying alternative to being a Social Justice Warrior, which just ends up hurting people's feelings ("A Christian Vision of Social Justice"):

Like a lot of people, I’ve tried to envision a way to promote social change that doesn’t involve destroying people’s careers over a bad tweet, that doesn’t reduce people to simplistic labels, that is more about a positive agenda to redistribute power to the marginalized than it is about simply blotting out the unworthy. I’m groping for a social justice movement, in other words, that would be anti-oppression and without the dehumanizing cruelty we’ve seen of late.

Some kind of political equivalent of Modern Monetary Theory that claims you could issue significant quantities of power to one group of people without making anybody else feel their power is threatened.

And he's actually found something interesting, in the work of a New Testament theology professor from evangelical Wheaton College and occasional Times contributor, Esau McCaulley (who is also African American, as Brooks characteristically doesn't say but shows us by including a picture, uncaptioned, that you can identify as him by comparing it with the portrait on his Times page), but of course he doesn't get it right.

In the first place, now that he's officially some kind of Christian himself, Brooks says he's discussing a "Christian social justice vision," but in fact it's Brooks's nearly annual Passover column, which I've been noticing since 2014 ("Passover without Jews," as I called it for the 2017 installment), in which he adverts to the holiday without apparently being conscious that it's coming (8 days from now), and misunderstanding its significance:

The Christian social justice vision also [in addition to respecting "the equal dignity of each person"] emphasizes the importance of memory. The Bible is filled with stories of marginalization and transformation, which we continue to live out. Exodus is the complicated history of how a fractious people comes together to form a nation.

It has obviously been appropriated into Christianity, but it belongs to Jews, and it is the simple history of how a people escaped slavery and learned to assert its autonomy and dignity, but honestly it never got any less fractious, right up till now. And it's very importantly a complex nation, whose distinctness is always heightened by the presence of aliens or "strangers" who must be protected and cherished, "for we were strangers in Egypt". Those two elements, the up-from-slavery narrative and the obligation to care for the stranger, are the things that make Exodus a social justice story, and are the parts Brooks always misses.

The particularly Christian idea from McCaulley is that racism should be regarded as a sin to be confessed and atoned for (which would make it a better Yom Kippur column, I guess):

McCaulley doesn’t describe racism as a problem, but as a sin enmeshed with other sins, like greed and lust. Some people don’t like “sin” talk. But to cast racism as a sin is useful in many ways.

The concept of sin gives us an action plan to struggle against it: acknowledge the sin, confess the sin, ask forgiveness for the sin, turn away from the sin, restore the wrong done. If racism is America’s collective sin then the tasks are: tell the truth about racism, turn away from racism, offer reparations for racism.

That's not quite accurate, in that McCaulley does describe racism as a systemic problem in other writing, like his fine Times column on the Ahmaud Arbery killing from May 2020,

Black folks need more than a trial and a verdict. Our problems are deeper, rooted not in the details of a particular case, but in distrust of the system charged with protecting us and punishing those who do us harm. This cynicism is well earned, arising out of repeated disappointments.

He doesn't as far as I can tell spend a lot of time in his writing telling white people how they should feel, so I can't say what he told Brooks in their interview, but I'd imagine he must have meant the sin concept more on an individual basis, as in each of us being born a sinner. His interests in the Jewish testament seem to be more theological in the strict sense, I mean God-centered, and appealing less to Exodus than the Judges-Samuel-Kings-Chronicles sequence—

I am not far from the ancient Israelites of the Bible. Instead of pinning their hopes on corrupt rulers, they articulated a theology of the kingship of God. The Psalms, Israel’s hymnbook, are full of passages that say things like, “My whole being will exclaim, ‘Who is like you, Lord? You rescue the poor from those too strong for them, the poor and needy from those who rob them.’”

When kings and rulers would not bring about justice, the disinherited put their hope in God. This is the root of black faith in this country...

So the idea I get from the idea of racism as a sin is the idea that it is something for each of us to search for in our hearts, not a "collective sin"—to which the biblical response would be to take a pair of goats, sacrifice one, and "cancel" the other, as in Leviticus 16:21-22,

Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task. The goat shall bear on itself all their iniquities to a barren region; and the goat shall be set free in the wilderness.

—but a personal one, which we can try to expiate by becoming "anti-racist", in the term favored by Ibram X. Kendi (who does cheerfully tell white people how they should feel), and by working in whatever way to fix the inequities of the system, and to offer reparations that actually repair, not guilt money but investment in a more equal future.

But for Brooks the white person is the central figure in the drama, dreading "cancelation", avoiding pain, and hoping for congratulation:

this vision does not put anybody outside the sphere of possible redemption. “If you tell us you are trying to change, we will come alongside you,” McCaulley says. “When the church is at its best it opens up to the possibility of change, to begin again.”

New life is always possible, for the person and the nation. This is the final way the Christian social justice vision is distinct. When some people talk about social justice it sounds as if group-versus-group power struggles are an eternal fact of human existence. We all have to armor up for an endless war. But, as McCaulley writes in his book “Reading While Black,” “the Old and New Testaments have a message of salvation, liberation and reconciliation.”

The struggle for justice ends with new life for me, and everybody will like me!

No comments:

Post a Comment