You know what they say about the 1960s, "If you can remember it, you probably weren't there"? There's something like that going on about inflation in the 1970s, as in this column by Barron's retirement columnist, Neal Templin:

When I was a young reporter in the 1980s, my newspaper gave me raises twice a year for a while. I’d like to tell you I earned the salary boosts through extraordinary merit, but all the reporters got them.

The reason: The inflation rate was so high then that it was considered a hardship to go a full year between raises. Amazing, huh?

After decades of restrained prices, it’s hard to remember what it was like living in the inflationary environment of the 1970s and 1980s. Prices shot up for gasoline, groceries, housing, you name it.

The spike in energy prices was particularly painful. I was driving a 1970 full-size Ford that got less than 10 miles to the gallon in city driving. Filling up became a hardship.

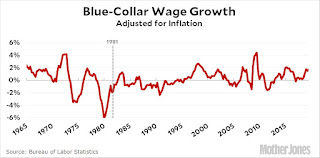

Well, for one thing he should have been driving a smaller car. Then there's those twice-a-year raises. If you were getting a raise twice a year you weren't the one with a problem. What Templin is telling us is that he lived through it without ever finding out what it was. As Kevin Drum was noting a couple of years ago (see chart at top), it was very different for blue-collar workers:

Wages went up and down in the 70s, but by the end of the decade hourly wages were a dollar lower than they had been at the beginning. In 1979 wages began to plummet, not getting back to positive growth until 1982. The rest of the decade is something of a train wreck for blue-collar workers, with wages mostly declining throughout the entire Reagan/Bush administration and not finally going positive until the middle of Bill Clinton’s administration. In reality, real hourly wages declined from $21.08 at the start of the Reagan era to $19.61 at the end of the Bush administration. That’s a loss of about $3,000 per year, or close to $6,000 per year in today’s money. If you add in the ’70s, it’s even worse: blue-collar wages dropped from $22.42 to $21.94. That’s a loss of $1,000 per year, or a little over $3,000 in today’s money. Put all this together, and blue-collar workers lost the equivalent of $9,000 in modern dollars, which represented a 13 percent decline in blue-collar wages over the course of a couple of decades. The entire period of the ’70s and ’80s was a catastrophe for blue-collar workers.

What we have now is not stagflation, people! Not, at any rate, in the United States. What we have now is people driving prices up because they've got plenty of money and are anxious to spend it.

Or, as they put it in the latest "Looks like pretty bad news how good the news is" piece from Wall Street Journal:

FRANKFURT—A booming U.S. economy is rippling around the world, leaving global supply chains struggling to keep up and pushing up prices.

I'm not even sure they even mean to say there's anything wrong with this. The burden of the article is that

- the annual growth rate in the US is running about 6% this year, 4% next year (7% this quarter compared to 2% in the Eurozone and 4% in China),

- wage growth is at 4% (less than 1% in Eurozone), and

- underlying inflation is "above 3%", meaning below 4%.

(Inflation was at 12% in 1974 and 14.5% in 1980, while wage growth rose from 6% to 8%, not close to keeping pace). And we know the inflation isn't making people unable to buy stuff because they can't stop buying stuff, thanks in part to the Biden administration's fiscal policy:

tangled global supply chains also play a role in driving global inflation, economists and central bankers are increasingly pointing to ultrastrong U.S. demand as a root cause.

“Are we crowding out consumers in other countries? Probably,” said Aneta Markowska, chief financial economist at Jefferies in New York. “The U.S. consumer has a lot more purchasing power as a result of fiscal policy than consumers elsewhere. Europe could be in a stagflationary scenario next year as a consequence.”

It may be 1976 somewhere, but it's not 1976 here. It's more like the 1950s out here, honestly. It's really virtuous inflation, of the kind we haven't seen in so long that we've forgotten what it looks like. As J. Bradford DeLong wrote last week,

and this week addingnot a 1970s like inflationary spiral—not melting the engine—but rather leaving rubber on the road as you rejoin the highway traffic at speed. Rejoining the highway traffic at speed is a good thing to do. Leaving rubber on the road is a necessary consequence of doing that. It’s stupid to complain about it.

it still looks to me much more like the post World War II and Korean War era recovery and structural readjustment discrete upward jumps in the price level....the princip[le] of prioritizing full employment and full recovery first, and rearranging the financial deck chairs later, would suggest that our current inflation is exactly what we want to see. Indeed, it is what we need to see in our economy, in which wages and prices are sticky downward to a considerable extent.

While the Federal Reserve has already announced the tools it will be deploying next year to slow it down: the tapering of the quantitative easing and the cautious rise in interest rates.

Make that "especially millionaires". People trying to tell you the real sufferers are the poor, who won't be able to afford short ribs, as if they could afford short ribs last year. Sorry, the real sufferers are the very wealthy watching the rate of return on capital go down. https://t.co/DYZWUHKuB8

— Condemn That Shit ASAP (@Yastreblyansky) December 19, 2021

Let's just hope those interest rate hikes stay cautious, and the professional rentiers don't get their way and tip us over into what WSJ and NYT would love to call a Biden Recession.

Cross-posted at No More Mister Nice Blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment