|

| Good cruise ship turning takes time—usually. Via. |

1. You know how Bill de Blasio ran for the New York City mayoralty on a promise to do something about the "inequality crisis" as he called it in the 2013 campaign:

“Right now, as we’re gathered this morning, one New Yorker is rushing past an attended desk in the lobby of a majestic skyscraper,” de Blasio began. “A few miles away, a single mother is also rushing, holding her two young children by the hands as they hurry down the steps of the subway entrance…” The first New Yorker is thinking about how to profit from the bull market in stocks; the second is trying to figure out how to pay her grocery bill.

And in the intervening years since he's been mayor every once in a while somebody pipes up to announce that he failed to do anything: from the not-at-all biased Manhattan Institute in 2017 to the not-at-all biased Manhattan Institute in late 2020. Well, I guess it wasn't that widespread. Still, de Blasio himself admitted just last month that he hadn't solved inequality in New York yet, in spite of having had eight whole years to do it.

On Wednesday, with his time in City Hall approaching its end, de Blasio sounded far less idealistic and admitted that his lofty promise to fix New York’s economic disparities remains unfulfilled.

“I don’t think anybody — literally, I don’t know a single person — who thought we were going to solve all the inequalities of society in four years or eight years,” he said in his daily morning briefing.

What a quitter, right? Not one single person? What about all his supporters at, you know, the Manhattan Institute, who were totally expecting him to fix inequality and so disappointed at his failure?

Anyway, guess what?

New York City narrowed the inequality gap between 2014 to 2019, defying a national trend, as the bottom half of earners steadily increased their share of income faster relative to wealthier ones, an analysis of annual state tax data by the Independent Budget Office shows.

According to the IBO, a non-partisan group, city tax filers in the bottom half of the income distribution who made about $4,400 to $37,800 saw their share of income distribution grow from 7.5% to 8.7% between 2014 and 2019. Those earning between $148,200 and $804,300 — who fall within the top 10% of earners — also saw their share increase during that time, but not as fast as the bottom half.

You can say it's not much, and you'll be right, but it's so amazing to me that it happened at all, over a five-year period, up until the moment the coronavirus arrived and the inequality began to shoot up again, as poor people lost work and wages and rich people saw their portfolios balloon in value. While it lasted, though, it was like if worldwide sea levels dropped half an inch over a five-year period, enormous progress! And the difference in income share may have only 1.2 percentage points, but it was a 15% absolute increase. And it happened, at least to some extent, because of the implementation of some Democratic policies

including a minimum wage hike, rent freezes for rent-regulated tenants, and his universal pre-K program. However, economists also pointed to other factors, like a robust economy and low unemployment, as playing important roles.

(Economists might have noted that the robust economy had something to do with low-wage workers having more spending money, pre-K teachers and aides had more jobs, parents of pre-K kids had more time and money, but economists don't always think of those things.)

That is, de Blasio, with the assistance of the City Council and the state legislature and even a reluctant Governor Cuomo, actually did do something (and would have done more, if not for Cuomo's resistance to taxing the very wealthy).

And a sign, perhaps, of a wider trend, that the whole neoliberal trend in US policy of the last 45 years or so, with its encouragement of increasing inequality could be at long last starting to reverse, as Nathan Newman is suggesting:

as I argued in How Dems Saved the Economy, we should not lose sight of the victories we have had in the last two years. It’s a policy victory that saved many people's lives and protected them from economic devastation, but it also reflects a political and philosophical victory that largely routed the conservative economic ideal.

Democratic victories in enacting the CARES Act, the American Rescue Plan, the infrastructure bill and moving the Build Back Better bill forward are all tremendous gains, reflecting the ways progressive ideas on the economy have become the mainstream in Democratic Party thinking and in society more generally.

That's nothing like a done deal, obviously: it's a tiny fragile embryo of a trend, and in constant danger of being snuffed out. The strictly political problems of Republican dominance aren't going away, even if The Former Guy is doing his best to wreck the party (delighted to hear that he's focused on engineering the defeat of Georgia governor Brian Kemp in a primary as Stacey Abrams renews her bid for the job), and they have the overwhelming advantages they've stacked up for themselves in years of redistricting legislative districts and naming judges and cultivating the studied pretense in the news media that they aren't dangerous anarchists.

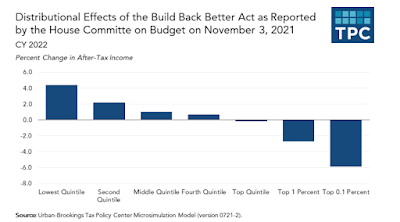

On the other hand, Build Back Better is itself going to have a powerful equalizing effect, as Newman notes,

and that will hold regardless of who wins the 2022 midterms, I think—Republicans aren't going to be able to turn these gains around in the same way and for the same reasons they couldn't turn around the Affordable Care Act.

And the rise of fascist danger is in its own right a sign of progressive success:

But the rise of fascist movements historically reflects the fundamental success of progressive movements and the failure of traditional conservatism, since corporate interests only fund fascists when their traditional political candidates fail to win over the public. Hitler was not legitimately elected by a majority of the German public; he was made Chancellor by corporate-backed parties that thought they could control him and defeat the German left during the crisis of the Depression. In fact, a bankrupt Nazi Party was bailed out financially by large industrialists to the tune of tens of millions of dollars precisely because those corporate interests thought their traditional political allies were too weak to win against the left.

One reason to get excited about this New York City story is the evidence that even if we lose the ability to act nationally, local progress can continue and grow, not just in New York and Los Angeles but also in Atlanta and Miami and Houston, perhaps. These turnarounds took place largely under the Trump administration, in spite of ferocious conservative power and media thumbsucking, and the reaction against it that put the Biden administration into office.

No comments:

Post a Comment